Malcolm

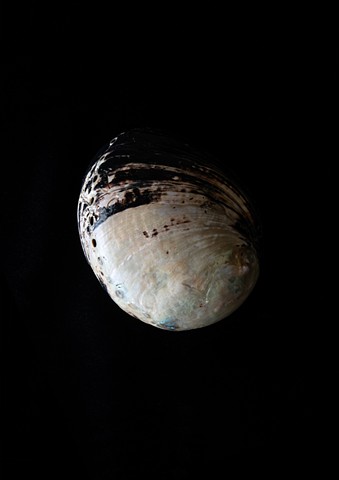

My long-term project Malcolm deals with themes of intergenerationality, care, mental health, and environmental and personal apocalypses. My dad (who from a young age I called by his name, Malcolm) was passionate about ecology and all forms of life. His schizophrenia meant that his decades-long fear of environmental destruction was sometimes obsessive, and he was convinced that space travel was imperative for our species to survive. He wrote many letters and political leaflets about these concerns and in 1980s Northern Ireland when my brother and I had to help him deliver them around the council estate they received very mixed responses.

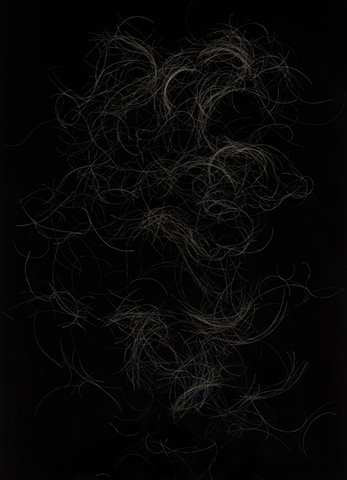

Recently the environmental devastation that he and most scientists had long feared, feels viscerally present. I think many of us feel that we are witnessing the beginning of the end for our planet. Malcolm died five years ago at 59, after a heart operation, and I discovered how the death of a parent can feel like the annihilation of part of yourself. In not discussing the intensity and complexity of grief, our culture makes it doubly painful and isolating. Malcolm had a ridiculous sense of humour, delighting in puns and taking us on adventures. But when we were at his house, sometimes his unpredictability meant emotional and physical neglect. His parents were eccentric, I think there was some isolation in his own childhood, and I’m sure that effected his parenting. My whole nuclear family has been diagnosed with various mental illnesses at different times. Much like scientific understandings of the planet’s climate, it is strange to think how differently ‘madness’ has been conceived of over just a few generations.

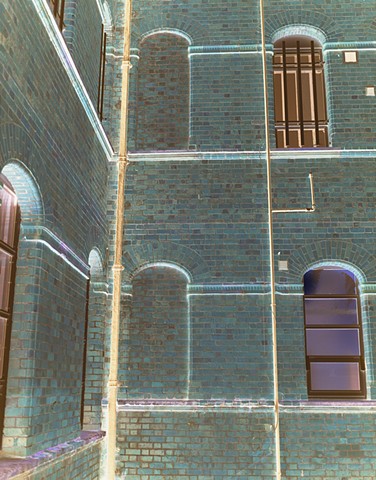

Terms like manic depression and schizophrenia have always felt to me like desperate attempts to categorize various experiences they cannot contain. I wonder how much of these ‘diseases’ are actually just extremes on the spectrum of all human experience. I’m interested in suppressed histories people deemed mad, and the burgeoning Consumer/Survivor/X-inmate movement. I identify with how this term expresses ambivalence toward the medical-model of madness (a word ‘mad-activists’ reclaim), in how it supports and dehumanizes different individuals. Malcolm had a fraught relationship with Northern Ireland Mental Health Services, and it is hard to know how much he was helped or harmed by their treatment.

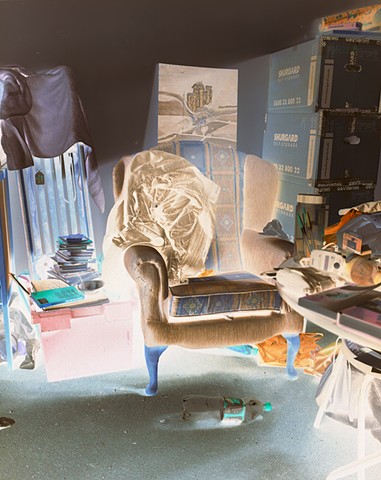

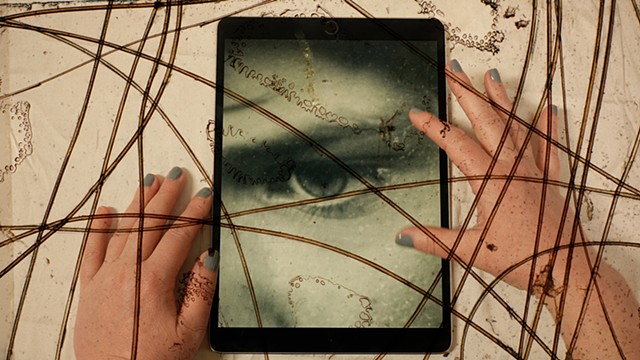

The variety of forms of image-making I use in Malcolm reflects the complexity and contradictions in these issues, in my father himself, and in our parent-child dynamic. My approaches include installation, moving image, and still images ranging from lumen photograms to medical documents, and from self-portraits to still lives. It may be impossible to fully ‘portray’ anyone or even truly know them, but this project gestures towards being the cosmology of a person.